Finding new life among the hidden worlds at the ‘Ends of the Earth’

During the late 1960s, John H Mercer set out on an epic adventure: To map the sequence of rock formations in Reedy Glacier, in West Antarctica.

On his field trip, the British glaciologist noticed a strange phenomenon: There were layers of sediments typical of those found at the bottom of lakes.

It led Mercer to come up with a new working hypothesis: Approximately 120,000 years ago, the high-altitude site where he was carrying out his research held lakes instead of glaciers.

Mercer’s logic implied that during warm periods, the West Antarctic ice sheet melts completely, only to re-form during cold periods.

Mercer explored this idea further in a scientific paper he published in 1968, but nobody paid attention. A decade later, Mercer published another paper in the science journal Nature.

“If the global consumption of fossil fuels continues to grow… atmospheric CO2 content will double in about 50 years,” he wrote.

“Climatic models suggest that the resultant greenhouse-warming effect will be greatly magnified in high latitudes… and could start rapid deglaciation of West Antarctica, leading to a 5m rise in sea level.”

The scientific community denounced Mercer as an attention-seeking alarmist.

From 1978, until his death nine years later, the British scientist struggled to get grants to support his research.

Mercer was a visionary, but his ambitious ideas did not fit with a commonly held consensus among climate scientists.

Up until the beginning of the millennium, most of them believed that Antarctica — the Earth’s fifth largest but least populated continent — was a stable bulwark against changes in ice.

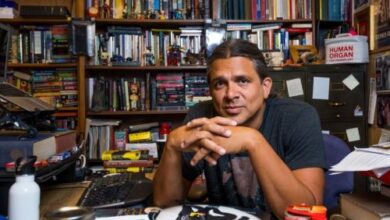

Today, American palaeontologist and evolutionary biologist Neil Shubin describes Mercer as “an amazing field geologist”.

“Mercer said the world is at a tipping point, and if we keep increasing global temperatures, we are setting ourselves up for dramatic changes with the ice in West Antarctica, and by extension, global sea levels,” the 64-year-old scientist explains from his office at the University of Chicago — where he is currently a professor of Organismal Biology and Anatomy.

“Mercer’s peers thought Antarctica was very stable. Unfortunately, though, as research continued over time, it turns out Mercer was probably right.

“Three decades ago in Antarctica, we were losing, say, 80 gigatons of ice per year. But now we are losing about 280 gigatons per year.”

Moving ice shapes the world

Shubin’s book examines how moving ice shapes the world. He notes, for instance, that polar regions encompass 8% of the total surface of the Earth and that almost 70% of all the planet’s fresh water is frozen in ice.

Expeditions to the polar regions are now a matter of urgency.

“The Arctic is heating five to seven times faster than the rest of the globe, and there are now open spaces of water where ice was previously,” he says.

“In Antarctica, melting ice is less visible to the naked eye.”

In fact, Antarctica is witnessing the slowest temperature rise on Earth, but for complex reasons. As the oceans warm, Antarctica’s surface temperatures stay relatively cool.

This disparity in temperature amplifies a wind current, which swirls around Antarctica and carries 170 times more water than all of the Earth’s rivers combined.

With that water comes heat. The change in the circumpolar current brings more warm seawater to the coast of Antarctica, causing the coastal glaciers to melt from below, where the ice meets the ocean.

The glaciers then fragment and collapse into the sea.

Shrinking glaciers, of course, mean rising seas.

The British Antarctic Survey along with the US Antarctic Program, have collaborated on research to help us understand those glaciers in West Antarctica.

“Specifically, with robots looking underneath the ice, and with satellite images, and with studies of the ice, both in the air and in the water. They confirm that in West Antarctica there is a lot to worry about,” says Shubin.

Drilling in ice in Antarctica has also shed light on another idea geographers and scientists have been speculating about since the mid-19th century: Underneath the ice of the region sit entire worlds sealed off from Earth’s surface.

We now have a detailed understanding of these hidden worlds, via decades of research that has been carried out by scientists from numerous countries at Lake Vostok.

The largest subglacial lake in Antarctica has a surface area of more than 14,000sq km and a depth of more than 800m.

Glaciologists have reasons to believe that Lake Vostok may have been separated from the world above for over 15m years, Shubin explains.

During the late 1990s, a group of Russian, French, and American scientists set off on an international science trip to drill a core to get down to Lake Vostok.

On that occasion, though, the team stopped drilling about 400ft above where they expected liquid water.

But even at that depth, the ice samples they recovered displayed special properties.

John Priscu, from Montana State University, later received one of those samples.

Putting them under high-powered microscopes, Priscu surmised that there were about 100,000 microbes per millilitre of ice.

Those findings inspired Priscu to hunt for more life elsewhere in Antarctica.

For logistical reasons Priscu decided to move his research to Lake Whillans: A subglacial lake in Antarctica that sits 480km from the South Pole.

Using a drill sterilised by UV light and hydrogen peroxide, Priscu and his team sampled the waters of Lake Whillans, which were then examined back in the lab.

DNA sequencing revealed nearly 4,000 species living in Lake Whillans under the ice.

The subglacial microbes were diverse, thriving, and part of a complex web of ecological interactions.

“These are living creatures that have been separated from the sun, for millennia, if not millions of years,” Shubin explains.

And these creatures exchange information with other lakes underneath.

“We don’t know much about these worlds and how these creatures survive. There is probably a wide diversity of microbial lifeforms that we can barely imagine under there.”

If life can thrive and survive under the ice in Antarctica, it might also be possible it can thrive in extraterrestrial environments too.

Shubin mentions Europa, the fourth largest of Jupiter’s 95 moons, and, Saturn’s moon, Enceladus: A small icy world that has geyser-like jets spewing water vapour and ice particles into space.

“Both of these places have ice on the exterior and fresh water underneath the ice, which make them two promising candidates for places in our solar system to expect microbial life,” Shubin explains.

“Understanding life under the ice in Antarctica gives us a model to think possible alien life outside our own planets.”

Closer to home, however, there are more urgent matters to be concerned about, Shubin warns.

Global warming means our planet is undoubtedly entering an era of uncertainty.

Shubin cites one scientific study which estimates that sea levels could rise as much as 10ft globally in the next century, if the planet warms more than three degrees Fahrenheit.

“Geological engineering is one option we might have to peruse if we cannot, as [a global community] get carbon emissions under control,” says Shubin.

“But the reality is that the choices we make for the future will make a difference. Not just for us. But for future generations.

“We need to keep global conversations alive and international science collaboration going,” Shubin concludes.

“Antarctica and the Arctic are warming, and polar treaties are straining as fast as ice melts and species disappear.

“Our fragile window for understanding the cosmos, the planet, and ourselves is closing, so we need to act now.”

Source link