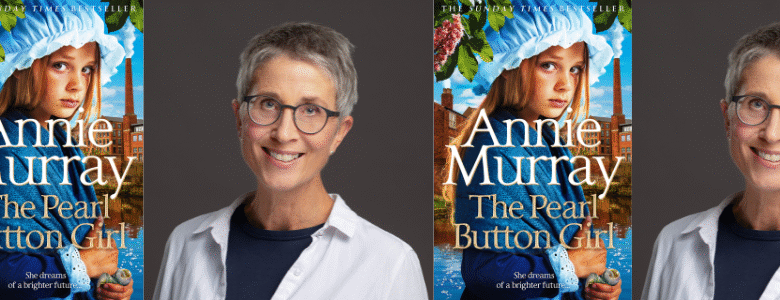

Author Interview: Annie Murray for the Pearl Button Girl

Over her career spanning thirty-odd years and the same number of novels, one thing has remained consistent in Annie Murray’s writing: Birmingham. Having spent portions of her life in the area, coupled with her West Midlands heritage, Murray’s work differs from the New York and London settings we’re used to in our fiction, instead finding itself in familiar locations like Bournville that are a stone’s throw from the Redbrick office. Murray’s latest offering, The Pearl Button Girl, is the first in a series about Victorian children living in Birmingham. I spoke to Murray on the phone about her inspiration, her research and her love of Birmingham.

Archie: Your latest novel, The Pearl Button Girl, is out in hardback now and paperback in February. How does it feel now that the book’s coming out?

Annie: It’s a nice feeling, but there’s that other feeling of ‘oh god, will anybody like it’. Also, by the time you publish a book it feels a bit distant from you – you’ve been through such a process with it. I’ve already moved onto writing the next book, which should give you an idea of the pace of it.

Surely you can’t have written over thirty novels without anyone liking them, though.

[Laughs] Yes, but there’s always a first time.

What inspired you to write The Pearl Button Girl, then?

Well, pretty much all the books I’ve written have been set in the twentieth century; with this particular historical genre, there’s an unwritten convention that you don’t really go beyond 1960 (though I have occasionally broken this rule). There’s a huge pressure in the industry to write about the Second World War, which I’ve done a lot of. But there comes a point where you just need to write something different.

What I hadn’t done before was explore the Victorian city, and a big reason for that is because there’s not anyone living today who could tell you about it from their perspective. (And I suppose that’s becoming true of the early twentieth century now, too.) I’ve always read about that period in just a generalised way; work pressures being as they are, what you learn is often on a need-to-know basis. I’ve never gotten to explore it in depth.

You mentioned that living sources for the period you’ve written about were obviously non-existent. How did you research for this novel without those sources?

I mean, the obvious one was books, in particular novels about working-class lives, such as The Nether World by George Gissing.

A crucial one for everything I’ve written about Birmingham has been maps. The city is ever-changing (even going back to the eighteenth century, there are poems whinging about how Birmingham is changing so quickly). I found one 1850s map online, took it to the central library and blew it up, and I ended up sticking all these A3 sheets together.

Oh, wow. I bet that took a while!

It definitely did. But it was of use in the end, thank goodness. I referred to this map instead of a historian because I’ve found that historians tend to tell you about something specific, in great detail, because they think it might be of use to you. And it’s too much sometimes! I needed a general map so I could do the honing in myself.

You’re very focused on writing books set in Birmingham and the West Midlands. What is it that compels you to write about this area specifically?

Just talking to people in [Birmingham]… I started to realize there was this whole other city in people’s minds

I’ve lived in Birmingham for a time, and there was – and still is – very little fiction written about the area. You know, I’m not a historian myself, but just talking to people in the area… I started to realise there was this whole other city in peoples’ minds, which was in large part due to the war. My mother was also from the Midlands, and talking to her too I got a sense that industry was the backbone of the area. Putting all those things together, I just got really fascinated to find out more. I’ve since moved away from Birmingham and spent a great deal of time apart from it, and I’ve sometimes worried that I’m not qualified to write about it; however, there’s so many people in Birmingham that aren’t from Birmingham.

Also, it’s not like you have many peers doing what you do – writing novels set in Birmingham – and telling you that you’re doing it wrong.

Yes. I mean, of the people that live in Birmingham… aside from a few that kept diaries, most were too busy and too exhausted to keep track. Anyway, I find that many novels use locations like the ‘New Jersey turnpike’ – I wanted to write about something familiar, like Bournville.

You’ve written several books under the pseudonym of Abi Oliver; does that name itself have any significance?

My grandmother was born in 1882, so actually did live towards the end of that Victorian period. The girls in her family all had the last name Oliver; but as they got married the name got lost; however, I quite liked the name so I thought I’d choose that. Meanwhile, the ‘Abi’ bit is just similar enough to ‘Annie’ without being too much so.

Can I ask why the pseudonym itself, too?

It’s really just a genre thing; it has a lot to do with marketing and branding. You have to treat your readers with a certain mantle of care – if you go in and write something that’s wildly different, it’s risky and they might not like it.

Recently I came across a Kierkegaard quote: ‘Everything a writer produces is posthumous’, in the sense that when a book takes on a new life for a reader it is dead to the writer, and the paths of reader and writer should never be allowed to cross. I wanted to know your thoughts on this – what you think about the relationship between writer and reader?

That’s a very interesting question. I’ve met some lovely people, primarily through my work in West Midlands libraries, so I really value that relationship. Plus, it’s always nice to meet people interacting with the books who are then interacting with the city. I do wonder, though, what it is my readers want from me; they read the books and identify with the people in them, and sometimes they want to tell me about their own lives as a result. But I just don’t think I’m the person for that, and I feel like I’m not what they’re actually looking for. Margaret Attwood said something I think about quite a bit: “Wanting to meet an author because you like his work is like wanting to meet a duck because you like pâté.”

I understand what you mean; you serve a purpose but sometimes people want more than that.

Some people are fascinated with the process of how I write – more interested than me, in some cases – and I take it at face value that they’ve chosen to be there because they want to be there.

I, for one, am interested!

Really?

I mean, half my degree is creative writing. Can I ask what it is you get out of the process of writing – why you’ve stuck by it all these years?

I grew up as an only child, and I had two imaginary friends: God, and my brother who didn’t exist. Living in that imaginary world helped me; now, the creativity of writing is really important to me.

Is it the escapism you value, then?

Yeah, maybe. I used to think it was about making sense of life – and perhaps it is, I’m not sure – but it’s a heightening of life, I think. I never really write about my own life anyway.

Do you have any advice for someone looking to go into a similar industry as you?

if you’re keen to [write], you will just do it… there was a point where I had to do all this writing around four under-5-year-olds. If you feel like you have a need to write, it’ll happen!

Well, it’s scary now because there’s so many people doing it. All I’d say is that if you’re keen to do it, you will just do it. For example, there was a point where I had to do all this writing around four under-5-year-olds. If you feel like you have a need to write, it’ll happen!

What’s difficult, though, is finding a niche; something distinctive. I found that, because my parents were adults during the Second World War, my books I wrote became a sort of family album. That was my niche. It also depends on what it is you’re writing; if you’re doing poetry, for instance, you absolutely need another job alongside that. But then that can also give you the freedom to write what you want when you want – not constrained by commercial pressure or anything.

Have you found yourself constrained by that pressure? Does being paid for your writing affect it in any way?

It makes you get on with it, that’s for sure. [Laughs] No, I find it pretty nice, and I enjoy it more every time. Every book has its own anxieties, but I know I can write each book because I’ve done it before.

It’s less of a step in the dark, I suppose.

Absolutely. What I’ve appreciated over the years is my ongoing relationship with the city, which has allowed me to write as much as I have about it.

The Pearl Button Girl is out on paperback now (order here). For more information, visit Murray’s official website.

Enjoyed this? Read more from Redbrick Culture here!

Book Review – I Who Have Never Known Men by by Jacqueline Harpmann

Source link