Bold Truths Book List — THE BITTER SOUTHERNER

When writer James Baldwin released his 1982 postmortem of the Southern Civil Rights Movement, a film entitled I Heard It Through the Grapevine, Baldwin lambasted Atlanta for conducting “the most extraordinary, spectacular makeup job in the history of the world.” Walking the streets of “the city too busy to hate,” Baldwin marveled at the gap between the Southern city’s reputation and reality, between the rise of civil rights statues and the fall of civil rights statutes, between the rise of white lies and the fall of Black truth.

“I was wondering,” sighed Baldwin, “what Martin Luther King would have thought of his Atlanta now?” Today, like so many other Atlantans, I echo Baldwin’s dismay amid the continuation of the South’s historical revisionism, amid our ongoing “extraordinary, spectacular makeup job” of reshaping the literal by removing the literary.

In this age of book bans, it’s so strange to be a Southern reader and writer, to live in a county named after Cherokee in a country that’s banning books about the Trail of Tears, to live in the shadow of Stone Mountain carved for Confederate generals in a country banning books about the Civil War, to live in a city where a larger-than-life mural of civil rights icon John Lewis towers over the community, only to watch down over his beloved constituents banned from reading about the Freedom Rides and the sit-ins.

To be a Southerner today is to live in a region anchored by the past in a country outlawing it. It is a project that seems, to us, impossible. It seems as absurd as telling the people of Seattle to ban books about the rain. It seems as ludicrous as telling the people of California to ban books about the ocean and the sun. We who were raised under Confederate flags, who swam in waters named Chattahoochee, do not have the luxury of forgetting, of denying America’s inconvenient truth.

This truth, when bound into books, is what so scares our citizens, is what instills local school board meetings with their manic, caustic atmosphere — hysterical gatherings horrified by reckonings about the roots of American prosperity. For now, whenever a Black woman reflects on the reality of the heel of Jane Crow on her neck, a panic ensues. Administrators change curricula. Librarians purge inventory. Politicians throw the book at people who publish books.

Yelling, lurching, screaming, America’s denialists do whatever they can to continue living in a society built by whips and chains, while believing it is all the result of a Protestant work ethic guided by the Invisible Hand.

All around us, our national psyche is now ravaged by untruths, by lies about vaccines, lies about the police, lies about tap water, lies about the “fake news” — by the Republicans’ “Big Lie” about the 2020 election, by the Democrats’ little lies about the severity of racial resentment and white supremacy. As former president Barack Obama wrote of his truth shading in his most recent memoir, A Promised Land: “I confess that there have been times during the course of writing this book, as I’ve reflected on my presidency and all that’s happened since, when I’ve had to ask myself whether I was too tempered in speaking the truth as I saw it, too cautious in either word or deed, convinced as I was that by appealing to what Lincoln called the better angels of our nature I stood a greater chance of leading us in the direction of the America we’ve been promised.”

A lie is a lie — whether told to harm, or to heal. Here, in Obama’s words one reads a sense that America is so allergic to the truth, so incapable of processing difficult realities about our past and present selves, that perhaps concealing is our only possible form of communication. It is this idea that is so thoroughly dismantled by Southern writers and Southern writing.

The blessing of Southern books, of Southern authors, is that we know our history is inescapable. We are, from an early age, taught to make our peace with hard truths, with all of its tragedy and beauty, with all of its devastation and diversity. And at our very best, our books embody the thorny work of creating an honest pluralism, of colliding and reconciling all our cultures and histories. Like the cuisine of New Orleans or Charleston, Southern literature is bubbling and boundless, stirring the French, the Spanish, the African, the Caribbean, the Native American influences into an uncompromising stew of creative genius.

Southern writers do not pretend that America’s sordid past is popular, they simply write it so well as to make reading about that past popular. This is what great art does, makes the untouchable graspable, renders the unspeakable elegiac. This is true not just of Southern writing, but of all great writing.

In her brilliant new biography Survival Is a Promise, Duke Professor Alexis Pauline Gumbs profiles Audre Lorde, who was a master of this craft. Describing the challenge of communicating across differences, Lorde once wrote, “I am reminded of how difficult and time-consuming it is to have to reinvent the pencil every time you want to send a message.” Yet this is exactly what Lorde did, and it’s exactly what so many Southern authors do time and again. They reinvent form and function to communicate across race, class, region, orientation, and gender. We reinvent genres, reinvent history, reinvent biography, reinvent children’s literature, reinvent fiction and nonfiction to hold all of our truths, and all of our histories.

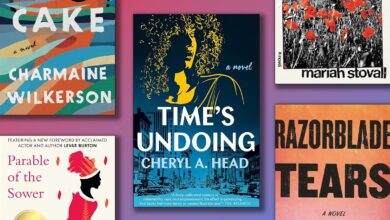

Right now, as our nation struggles so mightily to get to the bottom of its identity, it’s only right we look to the South. Here is a list of a few of our bravest, boldest, and most brilliant books of this year — writers who, like our greatest Southern traditions, have found a way to embrace the past, present, and future with fearless imagination and ingenuity. ◊